Scots Language Publishing Market Research

In which I apply my amateur skills to another field for which I am completely unqualified

To start with we should be clear there is no substantial market research into Scots language publishing.

Publishing Scotland, the Scottish publisher’s association, have carried out no research specifically into Scots language publishing

The Publishers Association, the leading (and most well-funded) member organisation for the UK publishing industry, have carried out no research

Nielsen, the organisation that administers ISBN numbers and the BookScan point of sales system, have carried out no market research.

There is no secret report, a hidden sheaf of papers, listing how many Scots language books have been sold each year, the best sellers lists, the numbers of titles and the relative sizes of market segments. The information compiled together does not exist.

No one knows for sure how many titles there are in total, how many sales, or how big the sector is. Its merely the gut feeling - small.

The information and communications sector which includes publishing is disproportionately illiterate in Scots compared to the rest of the Scottish population, their gut feeling and intuition cannot be relied upon.

I’m not at all qualified, but since no one else is doing it, I’ll have a go.

Not English

The first problem to face is that on the ISBN database of all books published in the UK and subsequently in the Amazon UK database, the Language field for Scots language books is often incorrectly set to “English”.

If a disinterested researcher obtained a list of all the books in the catalogue with the language set to “Scots” and reported it as being the entirety of Scots publishing, they would inadvertently ignore more than half of the market.

Over the past few years I have pulled together my own list of Scots books, more than 430 titles in total. They range from very broad Scots, urban Scots, quite English-like Scots, to dictionaries and books about Scots, there’s even a few Scots novelty colouring books. Whilst dictionaries, grammars and books about Scots are generally written in English, I have included them as “Scots books”. Generally the list is all books you might expect to find in the “Scots language” department of a high street bookshop if such a thing existed.

There’s a couple of notable absences from the list, best sellers from Douglas Stuart “Shuggie Bain” and “Young Mungo”, these do feature some Scots dialog, but the narrative is all standard English. Maybe its just my idiosyncrasy and iconoclasm, and no one would take exception to them being in the aforementioned “Scots Language” section of the bookshop.

Similarly, Oor Wullie and the Broons annuals, they are regularly best-selling books in Scotland, but I find the dialog is too inconsistent. It is a realistic portrayal of the code-switching between Scots and English in contemporary speech, but it doesn’t fit neatly into my paradigm. Sometimes Wullie says “canna” and sometimes he says “can’t”.

I have obtained a significant proportion of the books on the list, and have verified whether they are in English or Scots. Not all of them, because of money and space restrictions. A small number of books present uncertainty regarding whether they are written in Scots or not, and haven’t been purchased to resolve this.

There was a discussion on Facebook, which suggested that many of the books on my list were merely English with with Scots words swapped in, with no distinctly Scots grammar, and that is why they are labelled as English. I feel this is a bit too nuanced.

Amazon and ISBN don’t provide options for “good, well-constructed Scots”, “historically correct Scots” or “bad slang Scots”, or “not quite Scots”, or “Englishish Scots” or “Standard Scottish English with Scots words”. The categorisation is just broad guidance for the buying public with the two options “English” or “Scots” (or the secret third option, both - “English, Scots”).

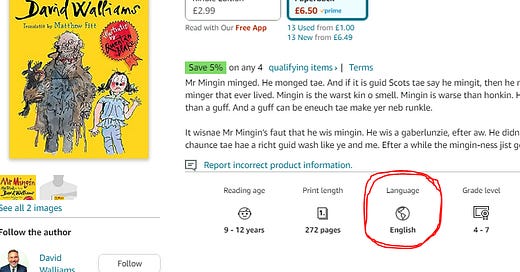

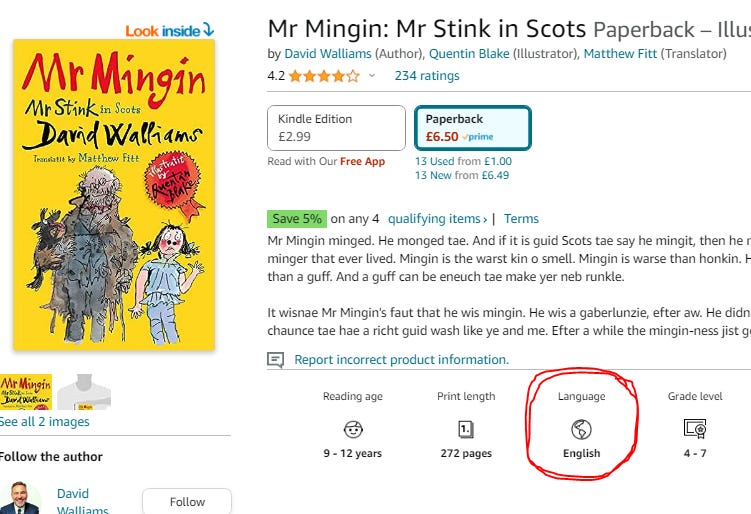

Award-winning Scots writer Matthew Fitt’s translation of David Walliams’ popular children’s book “Mr Mingin: Mr Stink in Scots” is currently labelled as English on Amazon and ISBN.

This is a brief extract:-

Rather than an in depth analysis of the grammar and spelling choices, we must ask the simple question - would the two million people who indicated that they understood Scots in the UK censuses agree with the categorisation that this is written in English?

The various reviews of this book on Amazon suggest that people who expected this prose to be English before buying the book are very disappointed.

Between half and three quarters of Scots books on my list are incorrectly categorised as being English. I suspect the dis-interested administrators at the publishers, Nielsen and Amazon haven’t paid attention or read the books at all.

List composition

This is a short overview of my list of Scots language books

440 Titles in total

186 different writers (although some books are anthologies where I’ve only noted one name)

145 Childrens titles (including 12 Gruffalos, 10 Asterix translations, and 8 Tintin translations and 5 Roalds Dahl)

92 Prose titles for adults (including 20 Bible translations)

131 Poetry titles and chapbooks

40 Dictionaries, grammars and books about Scots

9 Theatrical scripts

I reckon my list is very comprehensive, and estimate it covers more than 80% of the Scots literature currently in print.

The list can be found on Google Sheets here

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1r5xFJE2hZLd3I06spL-sHXAO0ED_6LHhBbH4G4hAj1w/edit?usp=sharing

If there are any Scots books that I’ve missed that are currently in print and available on Amazon, please let me know.

The National Library of Scotland have their own criteria for whether a book is written in Scots or not, they actually look at each book and make a judgement. Their catalogue comprises of more than a thousand books published over the same time span as my list. As a legal deposit library they separately record different editions of the same book (hardback, paperback, first edition, second edition, Waterstones exclusive edition, etc), so its likely our two lists match up better than a cursory glance would suggest.

I’ve noted the Scots regional dialect or language for each book in my list, the quantities are as follows:-

300 - Central

48 - Doric

31 - Ulster-Scots

13 - Orkney

13 - Shetland

11 - Urban

4 - English

Whilst it appears that Central Scots dominates the list, if we consider the size of the Scots speaking populations, Central Scots is under-represented. Orkney, Shetland and Ulster-Scots are over-represented.

Sales

With this list of books, we can turn to Amazon and note the “Best Sellers Rank” for each book. This will provide a rough indication of the number of sales of each book.

Of course it could be that there are more sales from physical bookshops, tourist giftshops, publishers’ and authors’ own websites, eBay and so on. The volume of sales from these places is currently unknowable. I can only work with what I’ve got and make sensible estimates and assumptions.

As mentioned earlier there is no substantial, authoritative market research from other sources. Researchers at Nielsen could cross-reference my list of books with the BookScan sales data to get more accurate figures.

Focusing on the Amazon Sales Rank, we must consider the rank at face value. There are over five million books listed by Amazon. For most of them the “Best Seller Rank” represents how recently a book was sold. There are only a few “Best Sellers”, most books sell just a handful of copies each year.

If two books each sell the same number of copies over a twelve month period, but the first book sold copies in a lump eleven months ago, and the second book sells them regularly over the year, then the second book will have a higher Best Sellers Rank than the first book.

By tracking the rank over time, we can actually see individual sales as they occur and blip the sales rank up.

Suppose a book has a “Best Seller Rank” of 1,000,000, it hasn’t sold any copies for a while, but if we look again and see that the sales rank has jumped to 200,000, then it has sold one copy. And over time we will see the sales rank slowly drift downwards.

Here we can see a book had a sales rank of around 1,000,000 then sold a single copy on Amazon at the start of June which put the sales rank up to 200,000, and then the rank slowly trailed off again. If Amazon sells one copy of this book in four months, we can estimate that there are three Amazon sales per year.

Here we can see two blips in the Best Sellers Rank, suggesting two sales during the observed time, so maybe six Amazon sales per year.

This analysis only works on mid-tier books, for more popular books, the line on the graph is too bumpy and the resolution is too poor to make out individual sales, some blips might be two or three copies sold in a week.

For the most popular books, an amateur like me can’t count individual sales and we must turn to maths. The relationship between volume of sales and sales rank follows a power law y = axk

If we know that best-selling “Shuggie Bain” with a sales rank of around 300 has sold around 100,000 copies in a year, and that a book with a rank of 3,000,000 sells about two copies per year, then the relationship between them would be:-

Sales volume = 10,000,000 * (sales rank^-1.12)

Its not a very good estimate for the very best selling books, but for everything below a rank of 100,000 its relatively accurate.

With more accurate information the constants in the equation could be adjusted to give a more reliable estimate.

Based on the figures we have, if we exclude “Shuggie Bain”, “Young Mungo” and the Broons, then Scots language books in total account for around 13,000 sales on Amazon each year.

If we use the current selling prices for each title, we can estimate that Amazon UK’s turnover from Scots language books is approximately £100,000

Amazon accounts for about 60% of UK book sales, so it follows that there are around 20,000 sales per year. Maybe I’ve got my maths wrong, there’s uncertainty. So with more confidence we can say that total sales are between 10,000 and 30,000 per year.

Although I don’t consider the Broons and Douglas Stuart’s books to be written in Scots, we might not mind them being included in a “Scots Language” section of a bookshop. If we include them in our sales estimate then Scots language book sales in the UK are around 150,000 units per year, and the value of the market is roughly £1,000,000

Segments and market share

Childrens books represent about 50% of sales

Adults prose books are about 20% of sales

Reference books are 11%

Poetry books and chapbooks are 9%

We can now look at the publishers who are represented in Scots publishing, the market share by volume of book sales. If we included the two Douglas Stuart books from Picador, then these best sellers would completely dominate with about 93% of the market.

If we ignore those books for not being written in Scots, the distribution of market share between the largest Scots language publishers is as follows:-

Itchy Coo - 38.7%

Picador - 11.7%

Luath - 8.1%

Kelpies - 7.2%

Canongate - 3.8%

Collins - 3.8%

Wee Books - 3.3%

Dalen - 1.7%

Tippermuir - 1.5%

Evertype - 1.0%

Langsyne - 0.9%

All the rest - 18.3%

Among the smaller publishers, there are a lot of self-publishers and minor presses who do not use ISBN numbers nor sell their books in major bookshops.

Comparison with English sales

Of course there are far more books written in English than in Scots and the market is far bigger. Its surprising that there are Scots-adjacent books anywhere near the best sellers lists. But if we look further down the field then more interesting comparisons can be drawn.

Medians and averages are funny old things. Suppose we looked at the top 5,000,000 most popular books on Amazon UK across all languages. We would expect the average and median rank (the mid-point) to both be precisely 2,500,000.

If Scots language books were dispersed as evenly as English across the top 5,000,000 best sellers then the average and median rank would also be 2,500,000. But when we check we find the average is 1,447,747, the median is even better at 998,326.

This suggests that despite the fewer number, Scots books perform better on average than English books.

Its difficult to recognise, but most books don’t sell many copies. There was a statistic that came out last year that whilst best-sellers can sell millions, the median book “in print” only sells 12 copies per year.

We have seen that books like Graeme Armstrong’s “Young Team” and Douglas Stuart’s works can be best sellers, but in the middle of the sales distribution, the less popular Scots books, are more popular than less popular English books.

If we count how many Scots book there are in each 500,000 rank segment, there is clear clustering towards the better selling end of the catalogue, more than random chance might predict.

98 Scots books were found in the top 500,000, if there was an average dispersion then we would only expect to find 44. Similarly 76 Scots books were found in the 500,000 to 1,000,000 bracket, still more than the 44 average expected.

Supply and demand

There are 1,460,000 people in Scotland who reported they could read Scots in the 2011 census. A quarter of the Scottish population are literate in Scots.

Do they buy Scots books? Where do they buy Scots books?

Based on our calculations earlier there is about one Scots book sale for every fifty readers. Can that really be correct?

Publishing Scotland reports that there are about 2,000 different titles published in Scotland each year, if there are fifty Scots titles then they makes up about one in every forty titles.

There are about 669 million book sales in the UK each year (including exports), so suppose it resolves to eight book sales per person. If the bi-lingual Scots speaker evenly divides their book buying between English and Scots, then we might expect around five million Scots book sales, not 30,000.

Earlier I mentioned that the information and communications sector, including publishing is disproportionately illiterate in Scots, perhaps institutionally they are fatally wounding Scots publishing.

I took a quick look at the Twitter feeds of a handful of Scottish Waterstones branches, checking out how many Scots language books they promoted compared to English language books.

The only books that got a mention were Douglas Stuart and the Broons, typically one of these for every 80 English books promoted. Although the Aberdeen branch did partially feature the “Itchy Coo book of Hans Christian Andersen’s stories in Scots” in one the background of a photograph. We should note that in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire more then 50% of the population reported they understood Scots and about 40% reported Scots reading ability, this population is not being served by their local branch of Waterstones.

If the mainstream high street bookshops are illiterate in Scots, and are inadvertently oppressing Scots publishing, then its a very awkward situation.

This month’s Best Selling Scots books

Its not possible to access a list of the best selling physical books in Scots on Amazon UK. There is a best-sellers list for Scots eBooks, but this relies on the ISBN language category and about half of top 30 list are eBook in Scottish Gaelic.

The Waterstones website has a ranked list of Scots books, although it is unclear where it gets its categorisation from. Although it can be filtered by genre (childrens books, poetry, art, etc), there are only 30 Scots books listed. There are notable absences from the list - Harry Potter in Scots, is listed as an English book. Waterstones also includes “A Rhyming Dictionary of the Scots Language” in their Scots best sellers list. This is a book which I have self-published, to the best of my knowledge only one copy has been distributed to Waterstones, it is unclear how this single sale two months ago could account for the #14 position in their chart.

In the absence of better ranked lists, here follows the Top 20 best selling Scots books based on Amazon Best Sellers Rank over the past four weeks:-

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stane

Matthew Fitt - Itchy Coo (2017)The Young Team

Graeme Armstrong - Picador (2021)The Gruffalo in Scots

James Robertson - Itchy Coo (2012)Ye Cannae Shove Yer Granny Off A Bus: A Favourite Scottish Rhyme

Kathryn Selbert - Kelpies (2018)Scots Dictionary: The perfect wee guide to the Scots language

Collins (2018)The Glasgow Gruffalo

Elaine C. Smith - Itchy Coo (2016)poyums

Len Pennie - Canongate Books (2024 - not yet published)The Gruffalo's Wean

James Robertson - Itchy Coo (2013)Scotland Slang Phrase Book

Summer autumn May - Independently published (2022)Room on the Broom in Scots

James Robertson - Itchy Coo (2014)Geordie's Mingin Medicine

Matthew Fitt - Itchy Coo (2007)Deep Wheel Orcadia: A Novel

Josephine Giles - Picador (2021)The Tale o the Wee Mowdie that wantit tae ken wha keeched on his heid Mackie Matthew - Tippermuir Books (2017)

The Wee Book o' Cludgie Banter

Susan Cohen - The Wee Book Company Ltd (2019)The Wee Book o' Pure Stoatin' Joy

Susan Cohen - The Wee Book Company Ltd (2019)The Wee Book a Glesca Banter: An A-Z of Glasgow Phrases

Iain Gray - Lang Syne Publishers Ltd (2012)A Doric Dictionary

Douglas Kynoch - Luath Press (2019)Haud Yer Wheesht!: Your Scottish Granny's Favourite Sayings

Allan Morrison - Neil Wilson Publishing (1988)The Wee Book o' fav'rite Scottish Words

Susan Cohen - The Wee Book Company Ltd (2020)Ya Wee Sh*te: Scottish Swear Word Colouring Book for Adults

Brittany David - Independently published (2021)

The Scots Language Publication Grant

The Scots Language Publication Grant provides assistance for publishing new work (including translated texts), reprinting existing historical or culturally significant work, and also effective marketing and promotion of existing and new work.

Its awarded to nine or ten projects each year, not all of these make it to publication

Twenty eight books in receipt of the award have been published and included in my list. Since the award was set up in 2019 a total of 146 Scots language books have been published, it follows that recipients of the Scots Language Publication Grant make up about 19% of the total Scots publishing output.

Gender split

Out of the writers listed about 35% are female and 62% are male, ‘other’ writers.

The titles produced by these writers have a split of roughly 31% female and 65% male.

By sales volumes the split is roughly 27% female and 57% male

Conclusions

I’ve made so many assumptions and estimates here that readers would be forgiven for disregarding the entire article. However, I’m sorry but I make no apologies, as there is no other substantial market research out there on this topic. This article is both the best and the worst available.

There are a handful of critical errors, such as relying entirely on Amazon Sales Rank to extrapolate sales data. Also there are a total of around 50,000 new titles published in the UK in any language each year, 2,000 of these titles are are published in Scotland. So, Scots books make up one in a thousand of UK titles and one in forty Scottish titles - which should we use for predicting what sales ought to be?

How reliable is the 2011 Scottish census, with its 1.9 million people who understand Scots?

Some publishers and writers might be grumpy that I have revealed this information here. Considering only around 30 people read this Substack, I don’t imagine errors in this article will cause much harm. Perhaps better equipped organisations will be triggered to carry out their own market research which will prove my assumptions wrong.