Further adventures with the Scottish Census

In my first look at the results of the 2022 Scottish Census back in May, I noticed a significant drop in the proportion of those under the age of 16 who reported they could speak Scots, perhaps a larger drop than in any other age bracket, and I put this down to a collapse in inter-generational transmission of the language.

In retrospect I might be mistaken, and another factor is at play.

The change in speakers

In the 2011 census the proportions of the Scottish population who reported they could speak Scots were as follows

30.04% Total

24.78% aged 3 to 15

28.74% aged 16 to 24

In the 2022 census the proportions who reported they could speak Scots were as follows

28.49% Total

21.16% aged 3 to 15

25.14% aged 16 to 24

The changes are as follows

Speakers

-1.55% Total

-3.62% aged 3 to 15

-3.60% aged 16 to 24

We might illustrate this with imagining an average school classroom with 30 children. In 2011, seven of those kids would be Scots speakers. In 2022, six would be Scots speakers.

Model families

Let us imagine a model family where both parents are Scots speakers (and English speakers). In this situation we might hope that inter-generational transmission occurs and the children grow up as Scots speakers, perhaps in 99% of cases.

The children would know that “haud yer wheesht” means shut up, “Ah dinna ken” means I don’t know, and “dinnae ye fash” means don’t you worry and all the rest of the words their parents used. And they would grow up with Scots being a natural part of their vocabulary, and an innate feel for when to use Scots, when to use English.

There might be rare cases where the kids reject Scots or their parents made a conscious decision not to speak Scots around their kids, but I reckon these sorts of cases would be rare.

Now let us imagine a second model family where both parents were English speakers or didn’t have any Scots. In this situation the kids might only have little exposure to Scots, the odd phrase here and there, a “dinnae dae that” overheard in the street or “bile ye heid” in the classroom.

Unless these second class of children had made a conscious effort they wouldn’t become fluent Scots speakers, so remain non-speakers 99% of the time.

In a third model family, where one parent is a Scots speaker and the other a non-speaker. It could go either way. Perhaps the kids would take on board their father’s turns of phrase, or perhaps they wouldn’t.

For the purposes of this model can we assume that 50% of kids in these hybrid families would grow up to report they they could speak Scots.

It could arguably be the case that in the hybrid households, the children become bi-lingual, fluent in Scots, and provide an avenue for Scots speaking to grow. But for the purposes of this model I will assume a 50% transmission rate.

In a situation with these three models of inter-generational transmission, and all other factor remaining constant, the proportion of Scots speakers in the population would stay constant, and wouldn’t drop 3.6% in ten years.

Birthrates

After last week’s substack article about the Stage 1 report and the “perilous state” of Gaelic, one commentator mentioned that in the Outer Hebrides, a last bastion for Gaelic speaking, people move to the islands and never bother to learn Gaelic. They are able to settle into the communities and survive with only speaking English.

The Comhairle nan Eilean Siar council website is all in English, the NHS Western Isles website is all in English. You don’t have to learn Gaelic to interact with the state. There is no compulsion to speak Gaelic.

Another commentator pointed out that his grandchildren were in a class at school where about 20% of the kids had Scottish parents and the rest had parents born overseas.

And in a third online discussion, this time about how the birthrates in countries that surround Scotland all seem to be a lot higher, and have been for more than a century. A commentator suggested that for Scotland a population of five million would be ideal, and people ought to have fewer children until this level is reached.

General overpopulation was given as the reason, but it was unclear why this ought to apply to Scotland and not to every other country in the world.

Could it be that intergenerational transmission isn’t broken, and the drop in Scots speaking ability among the young is entirely explained by Scot-speakers having lower birth rates than non-Scots speakers?

If this is the case then strategies to de-minoritise Scots would have to be quite different. Rather then relieving any supposed “oppression” of Scots that might make people less inclined to pass on the language, a more “in your face” strategy would be required, teaching and compelling non-Scots speakers to learn the language.

I don’t think a sufficient proportion of the political estate would ever have any interest in this.

Regions

First I am pulling out the Scots language ability by Age reports from the 2011 and 2022 censuses for each council region, to find out which areas have a large change in proportion and which don’t.

2022 percent Scots speakers among those aged 3 to 15 Percentage point change in proportion of those aged 3 to 15 who could speak Scots

Council area 2011 percent 2022 percent

Scots speakers Scots speakers

among those among those Percentage

aged 3 to 15 aged 3 to 15 point change

==============================================================

Eilean Siar 4.15% 6.64% 2.49%

North Lanarkshire 26.38% 26.75% 0.37%

West Dunbartonshire 25.73% 25.46% -0.27%

--------------------------------------------------------

North Ayrshire 30.32% 29.26% -1.06%

South Lanarkshire 23.39% 22.17% -1.22%

Renfrewshire 22.41% 20.63% -1.78%

East Renfrewshire 13.33% 11.52% -1.81%

Clackmannanshire 28.70% 26.83% -1.87%

West Lothian 26.01% 23.83% -2.18%

Glasgow City 24.69% 22.42% -2.27%

Inverclyde 24.02% 21.72% -2.30%

South Ayrshire 27.56% 25.19% -2.37%

Stirling 20.51% 17.93% -2.58%

Falkirk 28.95% 26.36% -2.59%

East Dunbartonshire 16.12% 12.97% -3.15%

East Ayrshire 33.62% 30.01% -3.61%

Highland 15.88% 12.23% -3.65%

Perth & Kinross 20.81% 17.15% -3.66%

Fife 28.43% 24.69% -3.74%

Dundee City 26.43% 22.32% -4.11%

Angus 26.68% 22.32% -4.36%

Dumfries & Galloway 27.51% 22.80% -4.71%

Scottish Borders 24.87% 20.05% -4.82%

Argyll & Bute 17.85% 12.99% -4.86%

Edinburgh, City of 16.93% 12.02% -4.91%

--------------------------------------------------------

Midlothian 26.05% 19.71% -6.34%

Aberdeen City 23.93% 17.21% -6.72%

East Lothian 23.26% 16.45% -6.81%

--------------------------------------------------------

Moray 34.81% 26.30% -8.51%

Aberdeenshire 35.52% 26.45% -9.07%

Orkney Islands 34.85% 24.27% -10.58%

Shetland Islands 42.12% 27.21% -14.91%

Going by each of the 32 local authority council areas, the average drop in the proportion of kids Scots speaking is -3.99%, the median drop is -3.63%, and the standard deviation is 3.38%. The range is between an increase of 2.49% and a drop of -14.91%, although most councils were in the range between -1.06% and -6.81%

Here I have tried to separate out the outliers:-

Eilean Siar has had a small increase in the proportion of Scots speaking school children, could this represent the migration of Scots speakers to the islands, from the mainland, among the English speaking migrants?

Both North Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire had almost no change to the proportion of schoolie Scots speakers/

At the other end of the spectrum, Moray, Aberdeenshire, Orkney and Shetland have had far larger reductions in the proportion of schoolchildren who speak Scots. These council areas have traditionally had a larger proportion of Scots speaker, as can be seen in both the 2011 census and the in the 1790 Statistical Account of Scotland.

Midlothian, Aberdeen City and East Lothian had larger than average drops in the proportion of those aged 3 to 15 who could speak Scots.

Birthrates

The 2022 Scottish Census results for birthrates and family size haven’t been released yet. So, at this point we can only play around with data from 2011.

Here is a list of the proportions of households with no children in 2011

Council Percent of 2011

households with no kids

Dumfries & Galloway 63.32%

Argyll & Bute 63.21%

Orkney Islands 63.13%

Scottish Borders 62.82%

Perth & Kinross 62.43%

South Ayrshire 62.05%

Aberdeen City 61.87%

Angus 61.45%

Eilean Siar 61.20%

Highland 60.99%

Moray 60.86%

Edinburgh, City of 60.29%

Fife 59.73%

Aberdeenshire 59.55%

Stirling 59.25%

East Dunbartonshire 59.19%

East Ayrshire 59.09%

Shetland Islands 58.99%

Clackmannanshire 58.98%

Midlothian 58.97%

North Ayrshire 58.53%

Falkirk 58.32%

South Lanarkshire 58.07%

East Lothian 58.06%

Dundee City 58.04%

Inverclyde 57.58%

Renfrewshire 57.08%

West Dunbartonshire 56.31%

Glasgow City 55.72%

North Lanarkshire 55.29%

West Lothian 54.93%

East Renfrewshire 54.86%Here the average proportion of households with no children is 59.38%, median 59.14%, standard deviation 2.46%, so its quite a tight range with no outliers.

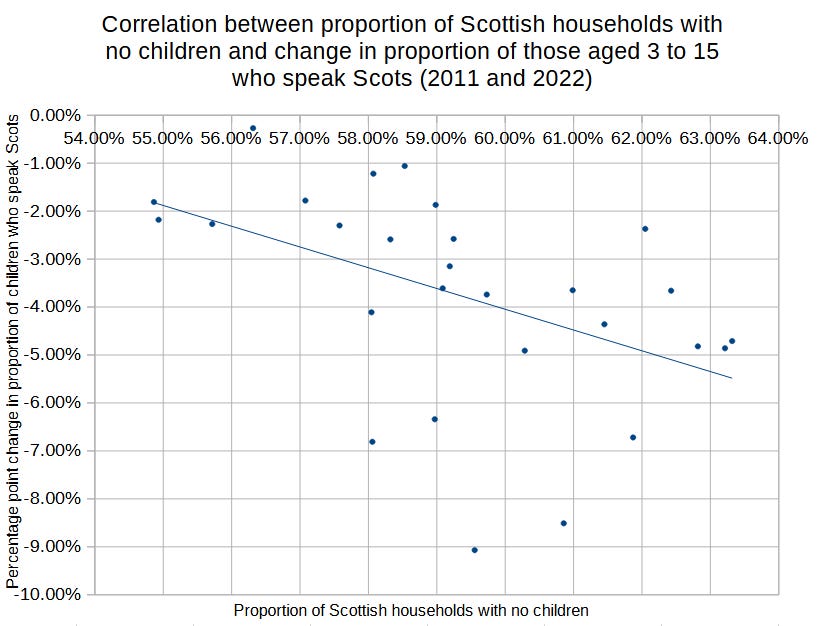

We can plot a graph of the proportion of households with no kids (in 2011) and the change in the proportion of Scots speakers aged 3 to 15 (between 2011 and 2022).

This graph cherry picks by ignoring the outliers, and gives a correlation coefficient of R = 0.53 so moderately strong. If we include the outliers, the correlation coefficient is R = 0.36.

This graph and correlation suggests that where there are more childless households there is a larger drop in the proportion of kids who speak Scots. And where there are more households with kids, there is a smaller drop.

This might suggest that inter-generational transmission of the language is a successful vector.

If Scots speakers were being out-bred by non-Scots speakers we might expect to see an inverse correlation - more kids - larger drop in Scots speaking. Have we satisfactorily disproved this theory?

Step changes

At this point in writing the article there was a discussion in the Scots Language Forum on Facebook about children being dissuaded from speaking Scots by their families. I know we’re already talk intergenerational transmission, but something just clicked, a small statistical epiphany.

Instead of looking at the change between the 2011 and 2022 censuses, we might look at the difference in the proportion of Scots speakers between the age of 3 and 15, and the proportion of Scots speakers among the entire population.

At the top of the article we noted in the 2022 census the proportions who reported they could speak Scots were as follows

28.49% Total

21.16% aged 3 to 15

25.14% aged 16 to 24

Thus the proportion of 3 to 15 year olds is 7.33% lower than the total proportion, the kids disproportionately speak Scots less than the rest of the population.

We can draw out the same figures for each local authority council region.

2011 proportion 2022 proportion

of 3 to 15 Scots of 3 to 15 Scots

speakers compared speakers compared

Council to other age groups to other age groups

===========================================================

Glasgow City 0.11% -2.16%

-----------------------------------------------------------

West Dunbartonshire -2.84% -5.06%

North Lanarkshire -2.65% -5.78%

Eilean Siar -3.88% -6.22%

Edinburgh, City of -5.00% -6.23%

Inverclyde -2.81% -6.35%

North Ayrshire -4.83% -6.60%

Argyll & Bute -4.60% -6.96%

Highland -6.75% -7.40%

Renfrewshire -4.58% -7.47%

Stirling -7.95% -7.64%

Clackmannanshire -6.73% -7.73%

Dumfries & Galloway -7.28% -8.08%

Dundee City -4.52% -8.20%

South Lanarkshire -5.38% -8.24%

East Renfrewshire -6.21% -8.45%

South Ayrshire -6.34% -8.53%

East Dunbartonshire -5.52% -8.62%

Falkirk -6.92% -8.72%

Fife -7.07% -8.98%

West Lothian -7.34% -8.99%

Shetland Islands -7.50% -9.39%

Scottish Borders -9.36% -9.52%

Perth & Kinross -10.25% -9.66%

Orkney Islands -6.70% -9.66%

East Ayrshire -7.27% -10.20%

East Lothian -8.05% -11.43%

Midlothian -8.15% -11.76%

--------------------------------------------------------

Angus -12.84% -13.28%

Moray -11.61% -13.64%

Aberdeen City -13.14% -15.63%

Aberdeenshire -15.23% -19.30%Here we can see that in the 2022 Scottish census, all council areas exhibited this step change in Scots language ability between the children and the rest of the population.

Glasgow performed best both in 2022 with only a -2.16% drop and in 2011 with 0.11% more kids reporting they could speak Scots than the general population.

The North Eastern areas Angus, Moray, Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire all had the largest step-change, with between 13.28% and 19.30% fewer children reporting they could speak Scots than the general population. This is significant, that 19.30% represents about six kids in a class of thirty who have lost their Scots language ability compared to other age groups.

Although another way to illustrate this is that if 28.49% of the population speak Scots, but only 21.16% of children speak Scots, then in around a quarter of all Scots speaking households the children are dissuaded from speaking Scots. Specifically in the North East, it is a third of Scots speaking households that might be dissuading their children from speaking Scots.

It is unclear if the data really supports the “inter-generational transmission failure” theory or the “Scots being out-bred by English” theory.

And now for a little politics

One of the old tropes from 2021 Twitter arguments about Scots was that it was some kind of Scottish nationalist scam, something about how it had been created so some people could claim to be more Scottish than others.

This was nonsense back in 2021. We had 2011 Scottish census data, and we had the results of the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, so I put together a series of graphs to see if there was a correlation between Scots language ability and the proportion of votes for each party in each constituency when I was going to write book about such matters.

It was somewhat surprising, but the strongest correlation was an inverse correlation between Labour voteshare and any Scots language ability Scots, and the weakest correlation was between Liberal Democrat voteshare and ability.

The Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients for the 2011 Scottish Parliament voteshare and the proportion of people with any Scots ability in the 2011 census were as follows:-

2011 Scottish Parliament election and 2011 Scottish census Scots speaking

SNP R = -0.21

Labour R = -0.50

Conservative R = +0.44

Liberal Democrat R = +0.18

number of constituencies = 73Now we have the data from the 2022 census, and the 2024 general election and the 2021 Scottish Parliament election. We can tabulate the various voteshares and proportions of people with any Scots language ability and calculate the Correlation Coefficients.

2024 General election and 2022 Scottish census Scots understanding

SNP R = +0.17

Labour R = -0.36

Conservative R = +0.45

Liberal Democrat R = -0.12

number of constituencies = 572021 Scottish Parliament election and 2022 Scottish census Scots understanding

SNP R = -0.13

Labour R = -0.37

Conservative R = +0.31

Liberal Democrat R = +0.02

number of constituencies = 73With three election / census combinations we can take an average for each political party.

We can see that in each case the strongest correlations are a negative correlation for Labour (average R = -0.41) and a positive correlation for Conservative (average R = +0.40)

For the SNP and Liberal democrats, sometimes there are weak positive correlations and sometime weak positive correlations. On average there is almost no correlation at all.

SNP average R = -0.06

Liberal Democrat average R = +0.03

Scots speaking among politicians and political types

There’s a video that keeps doing the rounds on Twitter, every six months or so, the frothing unionist types will share a video of Emma Harper MSP doing a video recorded in 2022, which was specifically a piece of outreach to sections of the population not usually catered to.

Those who disparage the Scots language usually hold it up as poor example of inarticulate spoken Scots.

There are 129 MSPs, if they spoke Scots to the same extent as the people who reported in the census, we might expect 39 MSPs to be Scots speakers.

If the 129 MSPs could read and write Scots to the same extent as the general population, we might find 26 Scots writers, but instead there is only Alasdair Allan who has any reputation for writing Scots.

On a similar note, among the 56 Scottish MPs, we might hope to find 17 speakers and 11 writers. Instead we find none.

Even amongst the non-political folk at Holyrood, I sent an email to the press office asking how many, or what proportion of the people in the press office could speak, read or write Scots (and / or Gaelic) and they refused to answer. I am going to take this refusal as an admission that they have none.

With the analysis above that correlates Conservative vote share with Scots speaking, we might hope that the MSPs and MPs in Conservative voting areas are most likely to speak or write Scots. These elected officials would be as follows:-

MPs - 2024 General election

Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk - John Robert Lamont

West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine - Andrew Bowie

Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale - David Mundell

Gordon and Buchan - Harriet Cross

Perth and Kinross-shire - Pete Wishart

MSPs - 2021 Scottish Parliament election

Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire - Rachael Hamilton

Aberdeenshire West - Alexander Burnett

Eastwood - Jackson Carlaw

Dumfriesshire - Oliver Mundell

Galloway and West Dumfries - Finlay CarsonIf we were trying to find Scots-literate politicians, these might be the right people to ask.

The raw data for the various correlations and graphs in this article are on a shared Google sheet here